This post could also be titled as “The Catch-22 of Telling People What to Do.” For in my work with people, topics such as

SUCCESS • HEALTH • WEALTH • SEXUAL FULFILLMENT

seem to come up all the time. Also questions such as :

“Am I in the right job for me?”

"Should I marry this person?"

"What can I do to make my body look better?”

“Is this a better career choice for me to make the money?”

In my practice of helping people come to their sense of Holistic Living these are just a few of the typical questions I tend to receive from clients who come to me for insight into the workings of their lives.

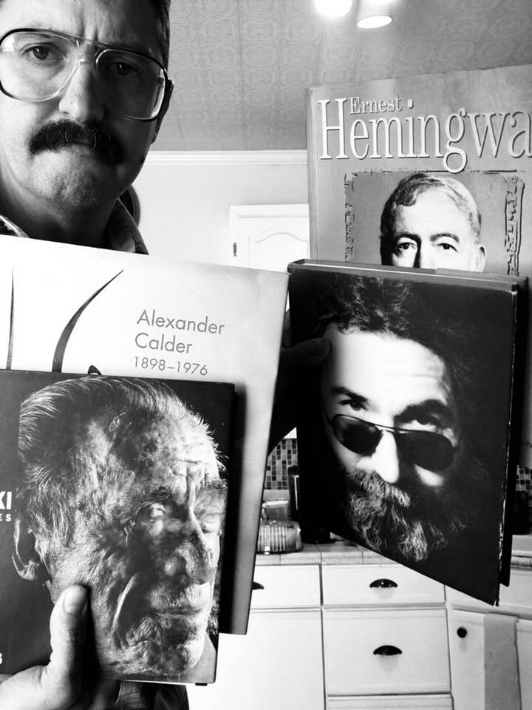

Years ago, in the 1980s, which were in my early days of working with clients in the use of self-help classes, one such course I designed and taught was the male-oriented Grooming Dynamics course (which to my surprise and delight worked equally well with female clients). Back then I would have done my damnedest to answer such questions as those posed above and done it with some sort of definitive “yes” or “no” response. After all, these people were paying me for that type of advice, right?

Over the years, an evolution and maturity have taken place in my practices of Life Coaching and Mentoring. With expanded listening techniques I now find myself being subtler, more cautious, in my answers and, I hope, more responsible in my approach toward my duties as a Mentor / Coach, for I’ve thought long and hard about what these duties really entail. Such as: Am I truly there (as a Mentor / Coach) to make up my clients’ minds for them concerning significant life decisions? More importantly, perhaps: What are the real consequences – for both the client and myself – of saying things that could alter a person’s life forever? As tempting as it may sometimes be to “help” a person through a genuinely difficult period, there is a thin line between truly helpful counsel and unwise interference with another person’s destiny.

I can think of an example that may show what I mean: Many years ago, a friend called to say he was signing up to join the Peace Corps and within the next few months would be traveling with a group through South America. He had never set foot outside the United States, so he was eagerly looking forward to this opportunity and began preparing for his trip. Just out of curiosity, and without telling him, I decided to check international news sources to find out what I could about the current situations in those countries – and was somewhat uncomfortable to find a host of challenging diplomatic, political, and / or military challenges occurring that could impact him while he was on this trip. Yes, there was the matter of safety that was being addressed by the Peace Corps, but by and large it was the sort of backdrop I myself would probably have avoided were I planning a trip and had this information.

What to do? My first reaction was to do the “altruistic” thing by telling him what I had found and then go on a volunteered rant of my advice on the matter, hopefully sparing him the problems of a potentially terrible trip. A few days later, before I had the chance to tell him what I found, he came in so excited about his plans, what it meant to his future, on and on . . . . His words caused me to take a step back from revealing my intel and to think about words that I have heard from many sources before, “Never volunteer advice or teaching uninvited.” These were words that seemed so timely in that situation. It made me reflect all the more deeply on my tendency to offer counsel to friends or family even when it wasn’t asked for. So I buttoned my lip and wished him the best trip possible.

Well, as it turned out, my friend’s trip proved to be a life-changing experience in ways neither of us could have foreseen. While he was in one of those remote regions of South America, a local villager had an accident and suffered serious injuries; my friend, who had already gone through American Red Cross basic first aid training and had a working knowledge of the Spanish language, became involved in the life-saving efforts until medical assistance could arrive. The scene, I could imagine, was one filled with chaos and anxiety. Yet for my friend this experience marked a key turning point in his life. Not only did it bring him into contact with an aspect of a foreign culture he wouldn’t have experienced otherwise, but it also served as a catalyst for his becoming more involved with humanitarian activities on a global scale. And there was a slim chance none of this would have even happened had I opened my mouth and volunteered my sage opinion.

A Fine Line

Since then, I’ve attempted to be much more conscious of how and when I go about freely dispensing advice to people. But what if a client asks me for advice on a major life decision? Does that violate a principle of noninterference?

If it becomes as strong a question as to send a flag up my emotional pole, then I have to stop and ask myself, “What then would my motivations for giving the advice be?” Sometimes giving advice makes a counselor, or Mentor, or Coach feel important and knowledgeable, but then the advice becomes ineffective. Sometimes it may even foster a non-therapeutic dependency such that the client does not learn how to solve problems himself or herself but merely how to ask for more advice. The sage saying, “Teach a man to fish,” comes to mind.

My goal with my clients is to be consciously nondirective. After all, who among us is truly wise enough to know all the ramifications of any given situation, whether acted upon or not? I know that no human is omniscient. We certainly cannot know all the variables of any situation, so we need to approach our discipline with a certain humility regarding our own grasp of “what is best” – or what isn’t.

I find myself asking more and more if a certain experience should be avoided simply because it may prove physically or emotionally difficult? How can we really know for sure what lessons a person might need to learn from a certain challenging situation? The history pages are filled with challenged individuals whose lives were changed – or whose lives, in turn, changed the world – by seemingly difficult experiences. Much as I hate to admit it, I fear that, 40 years ago, I probably would have done all I could to steer such a person away from potentially difficult situations.

So we find ourselves on the Razor's Edge as to what is the solution. Do we simply refrain entirely from giving advice or pointing the client in one direction or another?

Not necessarily. But first we realize that we cannot think about the clients questions from the viewpoint of our own values and well-being. The question has to be reframed.

First, I try to remember that I am consciously playing a role. My role could be as simple as a passenger in a car with a map on my lap of the destination. The driver of the car (the client) has come to a fork in the road. I can point out the different prongs in the forked road, with the amount of miles each has, as well as curves, hills, switchbacks, and scenic views each would have, but it is ultimately the driver that must decide which course to take.

Secondly I and the client are in a state of conscious investigation of our Emotional Intelligence. (That is, coming to recognize the part emotions play in the decision-making process and how that play of emotions might have unconscious factors attached that affect decisions in thoughts and behavior.)

Thirdly, I provide my clients with strategies for how to come to the Truth of their problems. I am not there to make up my clients’ minds for them, nor to tell them how to live their lives; rather, it’s to draw out of them accurate information vs. unconscious playback loops of what they believe to be best: help them make their own decisions by drawing out their own inner wisdom and intuition in situations.

An example to illustrate how this might work is: An individual comes to me, tells me he is an A-Type personality and asks whether he should marry someone who, it turns out, is also a heavily A-Type personality. Taking a simplistic and judgmental approach, I might well look at this situation and tell him that two A-type individuals forming a partnership could make for a fairly competitive or volatile combination and, for that reason, might best be avoided. But taking a more nondirective, non-coercive approach, I could instead engage the client in what he is looking for from this relationship. I could ask the client to point out the potential problems he could encounter along with the potential perks that could arise from such a union. Indeed, such competition and or volatility might prove to be the very thing that a given individual might want in a relationship. Once clarified it is the client’s decision as to which way to go with it.

I can recall hearing my teacher say: “If you want to end a relationship with such and such person, simply stop arguing with them. They’ll get bored and go search out someone else to do battle with!” The key here is not to tell the client what to do, but merely help to illuminate his choices.

Helping Clients Help Themselves

The other point I want to make, which is many times so simple or apparent that it is disregarded, is best illustrated by a quote from Douglas Adams, who said, “I may not have gone where I intended to go, but I think I have ended up where I needed to be.” Which is in keeping with the conversation between Alice and the Cheshire Cat, those fictional characters from the book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll.

Alice asks the Cat “Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?”

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where–” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

“–so long as I get SOMEWHERE,” Alice added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the Cat, “if you only walk long enough.”

There is no such thing as the one right choice. It is more to do with the uniqueness of each of us. We must learn to get to know and then honor our authentic selves; then comes a realization that at the root of the things we desire is the authentic self within. It is that driver, that evolutionary impulse that has driven humanity forward and expresses within us, through us, and as us; that spark that drives us to want to be ourselves and know ourselves through the symbols of our desires. Decoding the symbols leads us to who we are meant to be. This is the only way we can ever find true happiness and fulfillment.

In some ways, even more importantly: My job as an Ontologically-based consultant is to help clients to get in touch with their own reserves of intuition in situations and to draw upon those reserves when making their decisions regarding these situations. Like our fairytale characters Alice and the Cheshire Cat these archetype symbols prove a useful analogy. The symbol is never really intended to simply answer questions about major life decisions, but rather to provide a series of metaphorical images that could serve to unlock an individual’s own inner wisdom regarding those problems. By reflecting on a symbol that arises in response to a question, one begins to understand the hidden dynamics underlying everyday situations.

Archetype symbols have been with us for centuries, in every culture and on every continent. There is profound wisdom contained within them, that draws on unconscious resources about life or our hidden talents - if we could but learn to trust and tap into them by slowing down the mind chatter to accept this input when contemplating a decision; to be aware, to listen for that certain “yes!” whispering from deep within as you contemplate your options. More often than not, I find that people already know at an intuitive level the right thing to do – they’re just looking for an outside confirmation of that inner knowing.

How I’ve come to see my role as Mentor in the lives of people who come to me for advice or insight is to realize that each person that I engage with has a unique life, as vivid and complex as my own, with their own calling, which is a calling demanding to be drawn out and realized by them.

The stance I take regarding my role in this process isn’t popular with every one of my clients, especially those who are looking for someone to take responsibility for their lives. But with each passing year I’m convinced that this is the wisest approach both for them and myself. It leaves me with a clearer conscience about my impact on others’ lives and in my own role as a Mentor / Coach.

Aloha,